I'm going to take you on a journey of

prescribing medications for a person with several chronic diseases visiting their family doctor. Along the way we're going to make three stops.

- Seeing what medications the patient is already taking.

- Figuring out if a change is required.

- Picking the medication and making the change (or adding a new one).

One reason I'd like to take you on this journey, is to help you appreciate how well-designed tools make the job easier. If you've ever tried to fix something with a pair of pliers when you really needed a socket wrench, then you'll know what I mean.

Reviewing the list

As a family physician, I see people in my office with many chronic diseases (high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, osteoarthritis, depression, low back pain, obesity, etc.) who take quite a few medications. It's pretty common for somebody to have at least 10 chronic problems and 10 to 20 chronic medications. It's increasingly common for people to be on 3 or more blood pressure medications.

I need to refer to the medication list a few times during an office visit. Different

versions of the list can make each task easier. Initially I look at the list to get an

overview of what medications the person is taking.

What seems to be your problem today?

Then I look to see what problems might be needing some attention. Review lab. Talk to the patient. Look at recent reports from the emergency room or other specialists. Review phone call notes.

- Is the blood pressure controlled?

- Are the latest lab results on target?

- Is a preventive service due? (mammograms, Pap smear, colonoscopy, oil change, tire rotation)

It's time for a change

If one of those issues requires a new prescription, then I need to look at the medication list again to see medications are already prescribed for that problem.

Let's say that their blood pressure is not quite controlled and we need to make an adjustment in the medication.

First, I look at the list to see what high blood pressure medications the person is already taking. I have to read the list and ask myself for each medication, "is this for high blood pressure? or this one? or this one?..." It takes quite a while and a lot of mental effort (that's called "cognitive load"). It would be a lot smarter if I could just glance and see all the high blood pressure medicines adjacent to one another (by sorting the list). It would be even easier if I could see only all the high blood pressure medications (by filtering the list), just for a second.

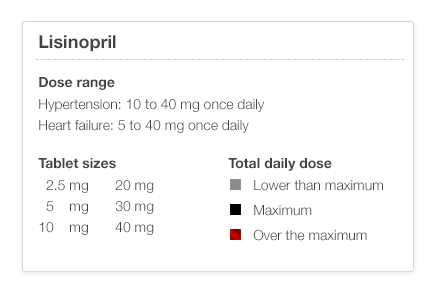

Then, among those medications, I need to figure out what dose the person is taking, and if that's the maximum dose. If we've already reached maximum dose, then I'll have to pick a new medication.

If not, then I can increase the dose of the medication that hasn't reached to maximum dose.

Take your pick

If I do need to pick a new medication, then I will look at the problem list to simplify things and to avoid new conflicts. I want to see what concurrent diesases (called "co-morbidities") the person has. If they also have migraines or irregular heartbeat, then I would choose a beta blocker or maybe a calcium-channel blocker. If they also have diabetes, that I might choose an ace inhibitor or and ARB (angiotensin-receptor blocker), if they're not already taking one of those drugs. In some cases, I avoid a particular drug (no Actos for you if you have heart failure already).

So you see, it's quite a bit of mental effort to just figure out how to add one more drug.

A well-designed EHR will lighten the cognitive load dramatically. All the required information needs to be

viewed in a single view without scrolling and without navigating around. At a minimum, that information includes the patient's active problem list, and all the current medications with those details visible. It's important to

not include more information than necessary, because the extra information just clutters the view and makes it harder to think or to notice what's important. If you've ever driven through an unfamiliar, busy urban highway intersection and had to read multiple signs at once, you'll appreciate the difficulty. Aircraft crew flight deck (control panels) design teams pay close attention to this, aiming for "

quiet dark".

Now you try it

I made a little interactive widget you can play with

here.

[Note: Blogger and my HTML tool Tumult Hype don't allow me to embed the widget. I guess I'll move to Squarespace hosting soon.]

Ask your self these questions:

- In the first screen, can you tell which medications are prescribed for high blood pressure (hypertension)?

- With the diagnoses visible, does it matter how the drug names are sorted?

- How much extra time does it take to find all the high BP medications in the different views?

- Can you tell if a medication dose is the maximum dose for that medication? (Hint: no, but I'll show you a cool way to do that in a later post.)