Sketching timelines

I first started thinking about graphical timelines when our team at University Missouri was working with our electronic health record vendor, Cerner, on a timeline for microbiology results (blood cultures and urine cultures). It was challenging to design timelines that were concise, intuitive, and effective.

A medication timeline will be far more helpful to me as a family physician, since I often struggle to understand a patient's medication history over the preceding years. it is difficult to find out when the medication was started or stopped, when it was was changed, and whether a medication had been tried in the past.

Fail early, fail often

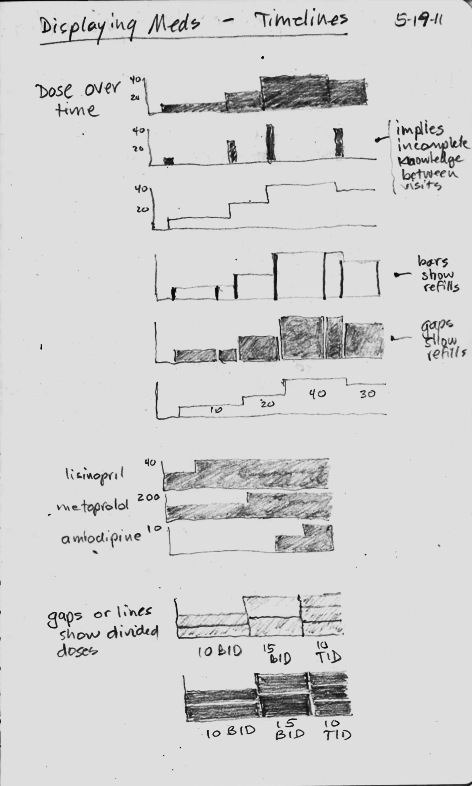

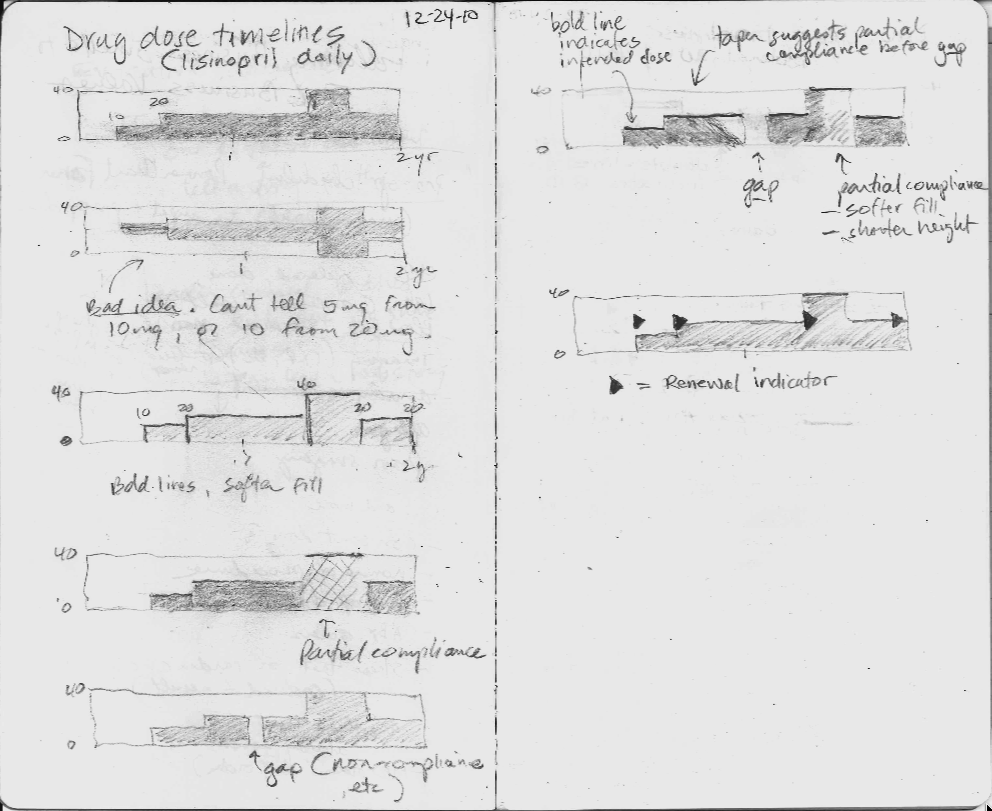

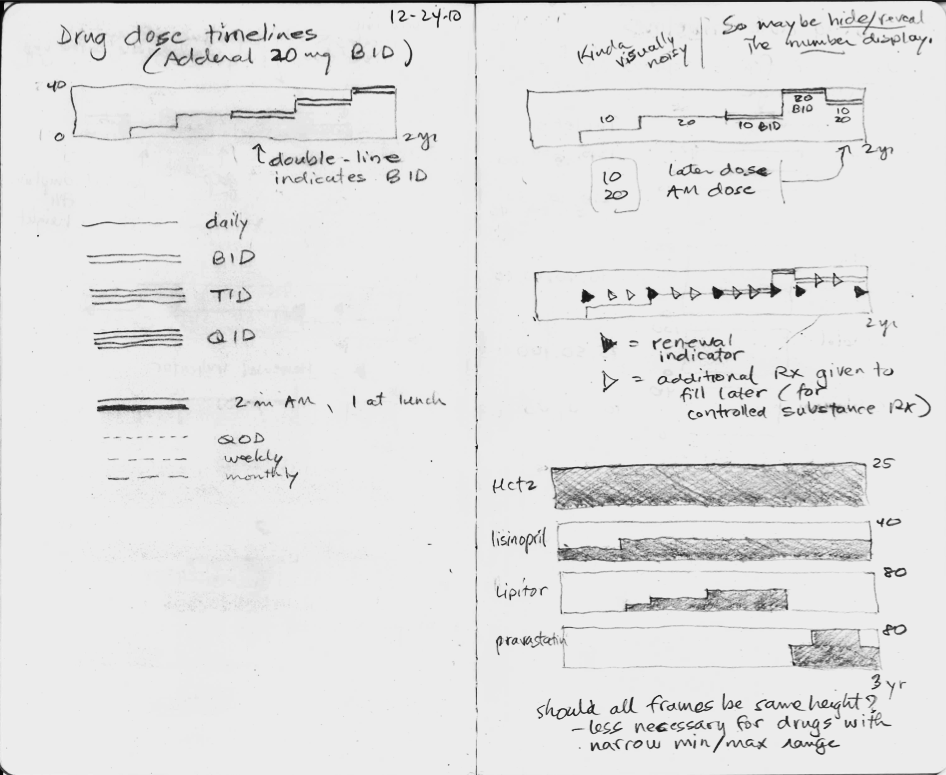

I made a number of failed pencil sketches that I've shown here that were ineffective at handling the cognitive challenge.

In the sketches, I explored using the height of the graph to display the dose, but none of the ideas really worked, mostly because they did not scale when the dose range could vary 16-fold or more. The dose of lisinopril can range from 2.5 mg to 80 mg daily, for instance.

Inspired by flight search

Then one day I was inspired by the beautiful and elegant visual design used by the flight search engine, Hipmunk. I immediately imagined an intuitive way to display a medication timeline.

In the process of making this online book, Inspired EHRs: Designing for Clinicians available freely online at inspiredEHRs.org, our design team had internal arguments about whether to make the timelines different hues of color, or whether to vary the line width of the bars. I think we made the right decision ultimately. By sticking with grayscale, we can then temporarily paint certain line categories different colors to give them visual meaning. For instance, all the hypertension drugs could be colored orange temporarily, to help the user see when the hypertension drug changes occurred.

Take the medication timeline for a spin

You'll find it here. See if it's intuitive you, or if there are some ways it could be improved. Let us know if you have feedback at inspiredEHRs.org/feedback. If you're aware of any EHR that is using a medication timeline, let us know at inspiredEHRs.org/feedback.